Take a Second Look: 25 Years and Counting

Maury Hall

Introduction

Take a Second Look (TASL) Boston Harbor winter bird counts have been a part of the Greater Boston birding scene for a quarter century. TASL is what local birders do in November, when the masses of sea birds finally arrive in the Harbor. And TASLing is the way to pass the winter months, after the Christmas Bird Counts and the new year list blitz are over and done with. In this article, Maury Hall, the TASL data compiler for the past 17 years, sketches a brief history of the project. Maury then explains the basic techniques of the counts, presents summary data for TASL's first quarter century, and provides brief accounts of water bird population trends or lack thereof.

History

The stimulus for the creation of TASL was "Black Sunday", December 15, 1976. This was the date the Argo Merchant, an aging Liberian tanker, went aground on Nantucket Shoals, southeast of Nantucket Island, spilling 7.6 million gallons of industrial heating oil into one of the most heavily used water bird wintering areas on the East Coast.

The impact of the spill on the avifaunal community was uncertain. The wintering populations of eider, long-tailed duck, alcids, and other species was thought to be high, but how high; 50,000 birds ? 500,000 birds? Also, complicating the assessment was the difficulty of estimating total mortality from only the number of oiled birds actually found.

Several local birders became concerned about these uncertainties: What if a similar tragedy occurred in their "backyard", Boston Harbor. They knew from their own observations that many birds over-winter in the Harbor but how many, and what species, and are they there in similar numbers every year? A search through Bird Observer records beginning in 1973 (inception year of Bird Observer) found that while rarities, like King Eider, appeared to be duly reported, more common species like Common Eider were clearly only sporadically reported. In some winters there were no reports of Common Eider in the harbor at all. Yet it was well known that thousands could be seen every winter in the Inner Harbor and just off Deer Island.

In 1978, at a party celebrating Bird Observer's first "Where To Go Birding" book (Where to find Birds in Eastern Massachusetts) the TASL project was hatched. Craig Jackson, Wayne Petersen, Leif Robinson, Bob Stymeist, Soheil Zendeh and others agreed that a series of systematic censuses of the Harbor was what was needed. Leif's suggested name, Take A Second Look (TASL) stuck. For Leif the name was a way of signaling that birding, as hobby, had grown past the point of listing species. We were now going to look at our subjects, the birds—really look at them. And looking meant counting common species, observing behavior, and keeping track of seasonal variations.

While some pilot surveys were made in 1978 and 1979, 1980 marked the official beginning of the TASL Boston Harbor bird census project. During the first two years surveys were undertaken in November, February, March and occasionally April. Beginning in 1982, a January count was added. After five years a decision was made to drop back to just one midwinter census in January. However, in 1988 the Massachusetts Audubon Society's Boston office, with a mandate to monitor the conditions of the Harbor prior to the "Harbor clean-up" provided an infusion of new volunteers to the TASL project. In subsequent years surveys were made in November, January, February, and sporadically in March.

2005 marked the 25th anniversary of this project. It therefore seems appropriate to report on our project and results.

Routes and counts

For TASL purposes, Boston Harbor extends along the coast from the eastern tip of Nahant south to Allerton Point in Hull. There are approximately 130 specific locations from which observations are made. We have tried to schedule the Sunday surveys around mid-morning high tides so that birds will presumably be closer to the observers. In order to maximize the synchrony of observations. 8 - 10 teams, each made up 1 to 4 people, work simultaneously. In general the Harbor is covered during approximately a four-hour window. To provide consistency we try to keep teams together and covering the same area as much as possible.

Participants are asked to count all visible water birds (i.e. ducks, geese, waders, shorebirds, alcids and gulls, with the exception of Herring, Ring-billed, and Great Black-backed) within their range. Raptors, seals, and relatively rare passerines and terrestrial mammals are also routinely reported. Also participants are requested to record the time at each site and to note birds flying to or from another team's area or birds that may be observed from another area. This information is evaluated during the compilation in order to minimize obvious double counts.

Results

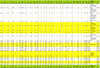

See the data summary tables. There are several factors that complicate the year-to-year comparability of our data set. Beginning with the involvement of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, participation in the censuses increased. This led to the splitting up of several areas that had previously been done by one team into 2 or 3 smaller sections each with a separate team. This resulted in a substantial increase in "party hours" as compared to the earlier surveys. The impact should be most pronounced for birds like loons and grebes that are normally seen singly rather than in flocks.

A second factor is weather. Some of the earlier surveys were undertaken during rain or snowstorms: less than optimal viewing conditions. In recent years, as our understanding of the best way to collect meaningful data evolved, planned surveys were postponed if inclement conditions were forecast.

Finally during the 1980s and early 1990s access to Deer Island in Winthrop and Long Island off Quincy was not possible. Both locations offer extensive viewing of Boston's Outer Harbor where many of the birds are found. While some of these birds can be counted from other sites, access to these two locations is essential for a full accounting.

A list of weather and accessibility limitations that impact an individual count are provided in the summary tables. These factors all contribute to a probable upward bias in number of birds seen in more recent years. Therefore observed increases in species abundance over time must be evaluated closely to validate the increase. On the other hand observed decreases are most likely real and may even underestimate the extent of decline. In order to address this issue, our tables show calculated party hours for each count.

Intrawinter trends

In order to investigate within winter (seasonal) trends we have used data only from years when we had November, January, and February counts which were either all unbiased by weather and/or missing sites, or were all biased in the same way (e.g. Deer Island missed in all three censuses). Twelve winters met this criterion. The average monthly dates for these years were November 20, January 13, and February 9.

The average number of party hours decreased from 35 hours per count in November to 32 in both January and February (Table 4). Likewise the average number of water-bird species and total number of birds seen both decreased from November to February. While there is a 9% drop in party hours between November and January there is a 15% drop in species and an 11% drop in total birds. However, between January and February party hours were constant but there was an additional 6% drop in species and 10% drop in bird abundance. Very likely much of the decrease in species and abundance is real accounting for rather than caused by the decrease in party hours (it takes less time to count fewer birds). On the other hand since many of the January and February counts are undertaken during frigid conditions we can't blame our volunteers for remaining at each of their sites a minute or two less than they might in milder temperatures and missing a few birds in the process.

The intrawinter trends appear to fall into three relatively distinct patterns. For most species (Red-throated and Common loon, Horned and Red-necked grebe, Double crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, scoters, Bufflehead, Red-breasted Mergansers, Long-tailed Duck, Black-bellied Plover, Sanderling, Dunlin, and Bonaparte's Gull) there is an approximate 50% drop in numbers between November and January and a further but more measured decrease from January to February. If one assumes that cormorant spp. are mainly Great Cormorants (which they probably are since most of these are silhouettes on the Outer Harbor Islands where this species is known to winter), then Great Cormorant falls into this category as well. Seal sightings also are highest in November.

A second pattern, observed in Brant and Common Eider, shows smaller decreases of approximately 10% between November and January with a similar additional decrease into February. The magnitude of the decrease is quite similar to the 9% decrease in party hours and as a result may be an artifact of it. Clearly, for these two species, abundances in November are a reasonably good predictor of abundances in February. This is also the case for Mute Swan and Purple Sandpiper which show no particular trend from November to February. The third pattern observed is for Canada Goose, American Black Duck, Mallard, Common Goldeneye and Greater Scaup. For these species the highest abundance is in January or (in the case of Greater Scaup) in February. We assume that these birds stay as far north (or inland) as possible until ice covers the inland waters forcing their flight south and east.

Interannual trends

Since January TASL counts have been undertaken continuously since 1982 and since by January the wintering waterfowl population is generally established, we use the January counts as the best indicator of inter-annual trends. Data from the November and February counts can be used to provide support for observed January trends.

A number of species show no indication of long-term change. Great Blue Heron, Black-bellied Plover, Sanderling, and Purple Sandpiper are not common in the Harbor in January but show much year-to-year fluctuation. In contrast, Common Eider and Bufflehead are two of the most abundant wintering species in the area. Bufflehead populations have always been relatively constant whereas eider populations appear to be much more variable. Part of this variability appears due to observer access (or lack thereof) to Deer and Long Islands as well as weather conditions. Since many Harbor birds are found in and around the islands at the mouth of the Harbor lack of access or poor visibility limits the accuracy of eider counts.

For three species, Dunlin, Red-breasted Merganser, and Common Goldeneye, the only observed population change appears over the past several years, possibly as a result of the comparatively severe winters.

Winter conditions may also be responsible for the recent very low abundances of American Black Duck and Brant. However, our data and observations from other areas in the region suggest that these species may be in a longer-term downward trend.

Bonaparte's and Black-headed Gull numbers also show a decrease over the past several years. The decrease of both is linked to the transfer of Boston's wastewater effluent discharge from Deer Island nine miles eastward into Massachusetts Bay in 2000. Both species were commonly observed feeding in the effluent plume at the tip of Deer Island or at the treatment facility itself, but have not been seen at these locations since 2000.

The population of Great Cormorants (identified Great Cormorants as well as birds recorded as cormorant species) has decreased markedly since the early 1980s. While November counts of Double-crested Cormorants have been highly variable, the number over-wintering in the harbor has been very low over the past decade as compared to the 1984 - 1995 period.

Lastly, Greater Scaup decreased dramatically from the early 1980s to the late 1990s. Over the past several winters the population has been variable but possibly showing an increase.

Not everything has been decreasing. Mallard, Canada Goose and Mute Swan all are displaying long-term increases. Red-throated Loon, Red-necked Grebe, Long-tailed Duck, White-winged Scoter, and Surf Scoter have been more commonly found in the harbor since the late 1990s. To some extent the same can be said of Common Loon and Horned Grebe.

Harbor Seals also have increased in the harbor since the late 1980s as they have region-wide. The increase is thought to be a population rebound after a distemper epidemic wiped out many seals in the Gulf of Maine region a decade earlier.

Conclusion

We intend this report to provide the reader with an overview of the goals and methods of the TASL project and a summary of its Boston Harbor water-bird data for the period 1980-2005. In addition, we have identified several possible species population trends.

The TASL Boston Harbor project began as a means of collecting baseline bird abundance data in the event of environmental tragedy. But what was unanticipated in 1980 was that the project would bracket the before and the after of the Harbor clean-up. We now realize, as we enter our next quarter century of monitoring, that our database represents a valuable tool in assessing changes that may be due to local conditions such as the Harbor clean-up, regional changes which may be due to year-to-year climate change, or to global conditions like climate change or other environmental factors. A later report will cover some of the more conjectural aspects of our analysis.

The success of this project is entirely due to the enthusiasm and perseverance of innumerable volunteers counting birds under often inhospitable conditions. Our thanks once again to all the route leaders and participants.

Maury Hall

Soheil Zendeh

Maury Hall, Project Manager / Environmental Scientist at Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) has been a lifelong birder. He was on the staff of Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1988 when MAS founded its Boston center and became involved in Boston Harbor monitoring. Maury at that time became involved with TASL data gathering and has been project coordinator ever since.

Maury lives in South Boston with his wife Kathleen and teen-age daughter Sarah, and is often seen birding along the South Boston shore or along the Charles River in Watertown.

Soheil Zendeh, born in Tehran, grew up in Tehran and Tangier, Morocco, arrived in Cambridge in 1961 as a college freshman, and started an auto repair shop in Cambridge, later Watertown. He began birding in 1973, never got a good look at the Newburyport Ross's Gull, got sick of driving to the north shore for birds, and began checking out local Boston spots in 1975, finding the "old puddle in East Boston" in 1976. He founded the Friends of Belle Isle Marsh with Craig Jackson in 1978, then co-founded TASL with Craig Jackson, Dave Lange, Wayne Petersen, Leif Robinson, Bob Stymeist and many others in 1979. He edited and published Belle Isle News until 2004, and published TASL News from 1980 to 1992. In 1996 he started TASL OnLine. He has also assisted Dick Veit and Ian Nisbet with Muskeget Island tern restoration.

Soheil lives in Lexington with his wife Christine and teen-age son Alex.